AGI by 2027 is strikingly plausible. GPT-2 to GPT-4 took us from ~preschooler to ~smart high-schooler abilities in 4 years. Tracing trendlines in compute (~0.5 orders of magnitude or OOMs/year), algorithmic efficiencies (~0.5 OOMs/year), and “unhobbling” gains (from chatbot to agent), we should expect another preschooler-to-high-schooler-sized qualitative jump by 2027.

Look. The models, they just want to learn. You have to understand this. The models, they just want to learn.

Ilya Sutskever (circa 2015, via Dario Amodei)

GPT-4’s capabilities came as a shock to many: an AI system that could write code and essays, could reason through difficult math problems, and ace college exams. A few years ago, most thought these were impenetrable walls.

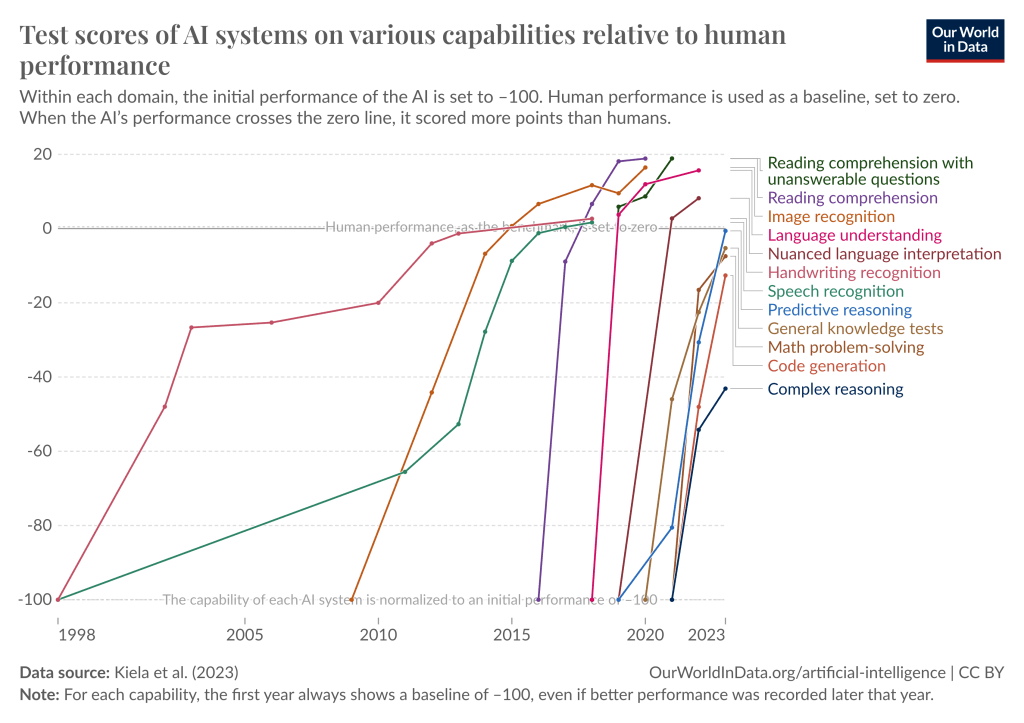

But GPT-4 was merely the continuation of a decade of breakneck progress in deep learning. A decade earlier, models could barely identify simple images of cats and dogs; four years earlier, GPT-2 could barely string together semi-plausible sentences. Now we are rapidly saturating all the benchmarks we can come up with. And yet this dramatic progress has merely been the result of consistent trends in scaling up deep learning.

There have been people who have seen this for far longer. They were scoffed at, but all they did was trust the trendlines. The trendlines are intense, and they were right. The models, they just want to learn; you scale them up, and they learn more.

I make the following claim: it is strikingly plausible that by 2027, models will be able to do the work of an AI researcher/engineer. That doesn’t require believing in sci-fi; it just requires believing in straight lines on a graph.

In this piece, I will simply “count the OOMs” (OOM = order of magnitude, 10x = 1 order of magnitude): look at the trends in 1) compute, 2) algorithmic efficiencies (algorithmic progress that we can think of as growing “effective compute”), and 3) ”unhobbling” gains (fixing obvious ways in which models are hobbled by default, unlocking latent capabilities and giving them tools, leading to step-changes in usefulness). We trace the growth in each over four years before GPT-4, and what we should expect in the four years after, through the end of 2027. Given deep learning’s consistent improvements for every OOM of effective compute, we can use this to project future progress.

Publicly, things have been quiet for a year since the GPT-4 release, as the next generation of models has been in the oven—leading some to proclaim stagnation and that deep learning is hitting a wall.1 But by counting the OOMs, we get a peek at what we should actually expect.

The upshot is pretty simple. GPT-2 to GPT-4—from models that were impressive for sometimes managing to string together a few coherent sentences, to models that ace high-school exams—was not a one-time gain. We are racing through the OOMs extremely rapidly, and the numbers indicate we should expect another ~100,000x effective compute scaleup—resulting in another GPT-2-to-GPT-4-sized qualitative jump—over four years. Moreover, and critically, that doesn’t just mean a better chatbot; picking the many obvious low-hanging fruit on “unhobbling” gains should take us from chatbots to agents, from a tool to something that looks more like drop-in remote worker replacements.

While the inference is simple, the implication is striking. Another jump like that very well could take us to AGI, to models as smart as PhDs or experts that can work beside us as coworkers. Perhaps most importantly, if these AI systems could automate AI research itself, that would set in motion intense feedback loops—the topic of the next piece in the series.

Even now, barely anyone is pricing all this in. But situational awareness on AI isn’t actually that hard, once you step back and look at the trends. If you keep being surprised by AI capabilities, just start counting the OOMs.

The last four years

We have machines now that we can basically talk to like humans. It’s a remarkable testament to the human capacity to adjust that this seems normal, that we’ve become inured to the pace of progress. But it’s worth stepping back and looking at the progress of just the last few years.

GPT-2 to GPT-4

Let me remind you of how far we came in just the ~4 (!) years leading up to GPT-4.

GPT-2 (2019) ~ preschooler: “Wow, it can string together a few plausible sentences.” A very-cherry-picked example of a semi-coherent story about unicorns in the Andes it generated was incredibly impressive at the time. And yet GPT-2 could barely count to 5 without getting tripped up;2 when summarizing an article, it just barely outperformed selecting 3 random sentences from the article.3

Comparing AI capabilities with human intelligence is difficult and flawed, but I think it’s informative to consider the analogy here, even if it’s highly imperfect. GPT-2 was shocking for its command of language, and its ability to occasionally generate a semi-cohesive paragraph, or occasionally answer simple factual questions correctly. It’s what would have been impressive for a preschooler.

GPT-3 (2020)4 ~ elementary schooler: “Wow, with just some few-shot examples it can do some simple useful tasks.” It started being cohesive over even multiple paragraphs much more consistently, and could correct grammar and do some very basic arithmetic. For the first time, it was also commercially useful in a few narrow ways: for example, GPT-3 could generate simple copy for SEO and marketing.

Again, the comparison is imperfect, but what impressed people about GPT-3 is perhaps what would have been impressive for an elementary schooler: it wrote some basic poetry, could tell richer and coherent stories, could start to do rudimentary coding, could fairly reliably learn from simple instructions and demonstrations, and so on.

GPT-4 (2023) ~ smart high schooler: “Wow, it can write pretty sophisticated code and iteratively debug, it can write intelligently and sophisticatedly about complicated subjects, it can reason through difficult high-school competition math, it’s beating the vast majority of high schoolers on whatever tests we can give it, etc.” From code to math to Fermi estimates, it can think and reason. GPT-4 is now useful in my daily tasks, from helping write code to revising drafts.

On everything from AP exams to the SAT, GPT-4 scores better than the vast majority of high schoolers.

Of course, even GPT-4 is still somewhat uneven; for some tasks it’s much better than smart high-schoolers, while there are other tasks it can’t yet do. That said, I tend to think most of these limitations come down to obvious ways models are still hobbled, as I’ll discuss in-depth later. The raw intelligence is (mostly) there, even if the models are still artificially constrained; it’ll take extra work to unlock models being able to fully apply that raw intelligence across applications.

The trends in deep learning

The pace of deep learning progress in the last decade has simply been extraordinary. A mere decade ago it was revolutionary for a deep learning system to identify simple images. Today, we keep trying to come up with novel, ever harder tests, and yet each new benchmark is quickly cracked. It used to take decades to crack widely-used benchmarks; now it feels like mere months.

We’re literally running out of benchmarks. As an anecdote, my friends Dan and Collin made a benchmark called MMLU a few years ago, in 2020. They hoped to finally make a benchmark that would stand the test of time, equivalent to all the hardest exams we give high school and college students. Just three years later, it’s basically solved: models like GPT-4 and Gemini get ~90%.

More broadly, GPT-4 mostly cracks all the standard high school and college aptitude tests.5 (And even the one year from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4 often took us from well below median human performance to the top of the human range.)

Or consider the MATH benchmark, a set of difficult mathematics problems from high-school math competitions.6 When the benchmark was released in 2021, the best models only got ~5% of problems right. And the original paper noted: “Moreover, we find that simply increasing budgets and model parameter counts will be impractical for achieving strong mathematical reasoning if scaling trends continue […]. To have more traction on mathematical problem solving we will likely need new algorithmic advancements from the broader research community”—we would need fundamental new breakthroughs to solve MATH, or so they thought. A survey of ML researchers predicted minimal progress over the coming years;7 and yet within just a year (by mid-2022), the best models went from ~5% to 50% accuracy; now, MATH is basically solved, with recent performance over 90%.

Over and over again, year after year, skeptics have claimed “deep learning won’t be able to do X” and have been quickly proven wrong.8If there’s one lesson we’ve learned from the past decade of AI, it’s that you should never bet against deep learning.

Now the hardest unsolved benchmarks are tests like GPQA, a set of PhD-level biology, chemistry, and physics questions. Many of the questions read like gibberish to me, and even PhDs in other scientific fields spending 30+ minutes with Google barely score above random chance. Claude 3 Opus currently gets ~60%,9 compared to in-domain PhDs who get ~80%—and I expect this benchmark to fall as well, in the next generation or two.

Counting the OOMs

How did this happen? The magic of deep learning is that it just works—and the trendlines have been astonishingly consistent, despite naysayers at every turn.

With each OOM of effective compute, models predictably, reliably get better.10 If we can count the OOMs, we can (roughly, qualitatively) extrapolate capability improvements.11 That’s how a few prescient individuals saw GPT-4 coming.

We can decompose the progress in the four years from GPT-2 to GPT-4 into three categories of scaleups:

- Compute: We’re using much bigger computers to train these models.

- Algorithmic efficiencies: There’s a continuous trend of algorithmic progress. Many of these act as “compute multipliers,” and we can put them on a unified scale of growing effective compute.

- ”Unhobbling” gains: By default, models learn a lot of amazing raw capabilities, but they are hobbled in all sorts of dumb ways, limiting their practical value. With simple algorithmic improvements like reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), chain-of-thought (CoT), tools, and scaffolding, we can unlock significant latent capabilities.

We can “count the OOMs” of improvement along these axes: that is, trace the scaleup for each in units of effective compute. 3x is 0.5 OOMs; 10x is 1 OOM; 30x is 1.5 OOMs; 100x is 2 OOMs; and so on. We can also look at what we should expect on top of GPT-4, from 2023 to 2027.

I’ll go through each one-by-one, but the upshot is clear: we are rapidly racing through the OOMs. There are potential headwinds in the data wall, which I’ll address—but overall, it seems likely that we should expect another GPT-2-to-GPT-4-sized jump, on top of GPT-4, by 2027.

Compute

I’ll start with the most commonly-discussed driver of recent progress: throwing (a lot) more compute at models.

Many people assume that this is simply due to Moore’s Law. But even in the old days when Moore’s Law was in its heyday, it was comparatively glacial—perhaps 1-1.5 OOMs per decade. We are seeing much more rapid scaleups in compute—close to 5x the speed of Moore’s law—instead because of mammoth investment. (Spending even a million dollars on a single model used to be an outrageous thought nobody would entertain, and now that’s pocket change!)

| Model | Estimated compute | Growth |

| GPT-2 (2019) | ~4e21 FLOP | |

| GPT-3 (2020) | ~3e23 FLOP | + ~2 OOMs |

| GPT-4 (2023) | 8e24 to 4e25 FLOP | + ~1.5–2 OOMs |

We can use public estimates from Epoch AI (a source widely respected for its excellent analysis of AI trends) to trace the compute scaleup from 2019 to 2023. GPT-2 to GPT-3 was a quick scaleup; there was a large overhang of compute, scaling from a smaller experiment to using an entire datacenter to train a large language model. With the scaleup from GPT-3 to GPT-4, we transitioned to the modern regime: having to build an entirely new (much bigger) cluster for the next model. And yet the dramatic growth continued. Overall, Epoch AI estimates suggest that GPT-4 training used ~3,000x-10,000x more raw compute than GPT-2.

In broad strokes, this is just the continuation of a longer-running trend. For the last decade and a half, primarily because of broad scaleups in investment (and specializing chips for AI workloads in the form of GPUs and TPUs), the training compute used for frontier AI systems has grown at roughly ~0.5 OOMs/year.

The compute scaleup from GPT-2 to GPT-3 in a year was an unusual overhang, but all the indications are that the longer-run trend will continue. The SF-rumor-mill is abuzz with dramatic tales of huge GPU orders. The investments involved will be extraordinary—but they are in motion. I go into this more later in the series, in IIIa. Racing to the Trillion-Dollar Cluster; based on that analysis, an additional 2 OOMs of compute (a cluster in the $10s of billions) seems very likely to happen by the end of 2027; even a cluster closer to +3 OOMs of compute ($100 billion+) seems plausible (and is rumored to be in the works at Microsoft/OpenAI).

Algorithmic efficiencies

While massive investments in compute get all the attention, algorithmic progress is probably a similarly important driver of progress (and has been dramatically underrated).

To see just how big of a deal algorithmic progress can be, consider the following illustration of the drop in price to attain ~50% accuracy on the MATH benchmark (high school competition math) over just two years. (For comparison, a computer science PhD student who didn’t particularly like math scored 40%, so this is already quite good.) Inference efficiency improved by nearly 3 OOMs—1,000x—in less than two years.

Though these are numbers just for inference efficiency (which may or may not correspond to training efficiency improvements, where numbers are harder to infer from public data), they make clear there is an enormous amount of algorithmic progress possible and happening.

In this piece, I’ll separate out two kinds of algorithmic progress. Here, I’ll start by covering “within-paradigm” algorithmic improvements—those that simply result in better base models, and that straightforwardly act as compute efficiencies or compute multipliers. For example, a better algorithm might allow us to achieve the same performance but with 10x less training compute. In turn, that would act as a 10x (1 OOM) increase in effective compute. (Later, I’ll cover “unhobbling,” which you can think of as “paradigm-expanding/application-expanding” algorithmic progress that unlocks capabilities of base models.)

If we step back and look at the long-term trends, we seem to find new algorithmic improvements at a fairly consistent rate. Individual discoveries seem random, and at every turn, there seem insurmountable obstacles—but the long-run trendline is predictable, a straight line on a graph. Trust the trendline.

We have the best data for ImageNet (where algorithmic research has been mostly public and we have data stretching back a decade), for which we have consistently improved compute efficiency by roughly ~0.5 OOMs/year across the 9-year period between 2012 and 2021.

That’s a huge deal: that means 4 years later, we can achieve the same performance for ~100x less compute (and concomitantly, much higher performance for the same compute!).

Unfortunately, since labs don’t publish internal data on this, it’s harder to measure algorithmic progress for frontier LLMs over the last four years. EpochAI has new work replicating their results on ImageNet for language modeling, and estimate a similar ~0.5 OOMs/year of algorithmic efficiency trend in LLMs from 2012 to 2023. (This has wider error bars though, and doesn’t capture some more recent gains, since the leading labs have stopped publishing their algorithmic efficiencies.)

More directly looking at the last 4 years, GPT-2 to GPT-3 was basically a simple scaleup (according to the paper), but there have been many publicly-known and publicly-inferable gains since GPT-3:

- We can infer gains from API costs:13

- GPT-4, on release, cost ~the same as GPT-3 when it was released, despite the absolutely enormous performance increase.14 (If we do a naive and oversimplified back-of-the-envelope estimate based on scaling laws, this suggests that perhaps roughly half the effective compute increase from GPT-3 to GPT-4 came from algorithmic improvements.15)

- Since the GPT-4 release a year ago, OpenAI prices for GPT-4-level models have fallen another 6x/4x (input/output) with the release of GPT-4o.

- Gemini 1.5 Flash, recently released, offers between “GPT-3.75-level” and GPT-4-level performance,16 while costing 85x/57x (input/output) less than the original GPT-4 (extraordinary gains!).

- Chinchilla scaling laws give a 3x+ (0.5 OOMs+) efficiency gain.17

- Gemini 1.5 Pro claimed major compute efficiency gains (outperforming Gemini 1.0 Ultra, while using “significantly less” compute), with Mixture of Experts (MoE) as a highlighted architecture change. Other papers also claim a substantial multiple on compute from MoE.

- There have been many tweaks and gains on architecture, data, training stack, etc., all the time.18

Put together, public information suggests that the GPT-2 to GPT-4 jump included 1-2 OOMs of algorithmic efficiency gains.19

Over the 4 years following GPT-4, we should expect the trend to continue:20 on average 0.5 OOMs/yr of compute efficiency, i.e. ~2 OOMs of gains compared to GPT-4 by 2027. While compute efficiencies will become harder to find as we pick the low-hanging fruit, AI lab investments in money and talent to find new algorithmic improvements are growing rapidly.21 (The publicly-inferable inference cost efficiencies, at least, don’t seem to have slowed down at all.) On the high end, we could even see more fundamental, Transformer-like breakthroughs22 with even bigger gains.

Put together, this suggests we should expect something like 1-3 OOMs of algorithmic efficiency gains (compared to GPT-4) by the end of 2027, maybe with a best guess of ~2 OOMs.

The data wall

There is a potentially important source of variance for all of this: we’re running out of internet data. That could mean that, very soon, the naive approach to pretraining larger language models on more scraped data could start hitting serious bottlenecks.

Frontier models are already trained on much of the internet. Llama 3, for example, was trained on over 15T tokens. Common Crawl, a dump of much of the internet used for LLM training, is >100T tokens raw, though much of that is spam and duplication (e.g., a relatively simple deduplication leads to 30T tokens, implying Llama 3 would already be using basically all the data). Moreover, for more specific domains like code, there are many fewer tokens still, e.g. public github repos are estimated to be in low trillions of tokens.

You can go somewhat further by repeating data, but academic work on this suggests that repetition only gets you so far, finding that after 16 epochs (a 16-fold repetition), returns diminish extremely fast to nil. At some point, even with more (effective) compute, making your models better can become much tougher because of the data constraint. This isn’t to be understated: we’ve been riding the scaling curves, riding the wave of the language-modeling-pretraining-paradigm, and without something new here, this paradigm will (at least naively) run out. Despite the massive investments, we’d plateau. All of the labs are rumored to be making massive research bets on new algorithmic improvements or approaches to get around this. Researchers are purportedly trying many strategies, from synthetic data to self-play and RL approaches. Industry insiders seem to be very bullish: Dario Amodei (CEO of Anthropic) recently said on a podcast: “if you look at it very naively we’re not that far from running out of data […] My guess is that this will not be a blocker […] There’s just many different ways to do it.” Of course, any research results on this are proprietary and not being published these days.

In addition to insider bullishness, I think there’s a strong intuitive case for why it should be possible to find ways to train models with much better sample efficiency (algorithmic improvements that let them learn more from limited data). Consider how you or I would learn from a really dense math textbook:

- What a modern LLM does during training is, essentially, very very quickly skim the textbook, the words just flying by, not spending much brain power on it.

- Rather, when you or I read that math textbook, we read a couple pages slowly; then have an internal monologue about the material in our heads and talk about it with a few study-buddies; read another page or two; then try some practice problems, fail, try them again in a different way, get some feedback on those problems, try again until we get a problem right; and so on, until eventually the material “clicks.”

- You or I also wouldn’t learn much at all from a pass through a dense math textbook if all we could do was breeze through it like LLMs.23

- But perhaps, then, there are ways to incorporate aspects of how humans would digest a dense math textbook to let the models learn much more from limited data. In a simplified sense, this sort of thing—having an internal monologue about material, having a discussion with a study-buddy, trying and failing at problems until it clicks—is what many synthetic data/self-play/RL approaches are trying to do.24

The old state of the art of training models was simple and naive, but it worked, so nobody really tried hard to crack these approaches to sample efficiency. Now that it may become more of a constraint, we should expect all the labs to invest billions of dollars and their smartest minds into cracking it. A common pattern in deep learning is that it takes a lot of effort (and many failed projects) to get the details right, but eventually some version of the obvious and simple thing just works. Given how deep learning has managed to crash through every supposed wall over the last decade, my base case is that it will be similar here.

Moreover, it actually seems possible that cracking one of these algorithmic bets like synthetic data could dramatically improve models. Here’s an intuition pump. Current frontier models like Llama 3 are trained on the internet—and the internet is mostly crap, like e-commerce or SEO or whatever. Many LLMs spend the vast majority of their training compute on this crap, rather than on really high-quality data (e.g. reasoning chains of people working through difficult science problems). Imagine if you could spend GPT-4-level compute on entirely extremely high-quality data—it could be a much, much more capable model.

A look back at AlphaGo—the first AI system that beat the world champions at the game of Go, decades before it was thought possible—is useful here as well.25

- In step 1, AlphaGo was trained by imitation learning on expert human Go games. This gave it a foundation.

- In step 2, AlphaGo played millions of games against itself. This let it become superhuman at Go: remember the famous move 37 in the game against Lee Sedol, an extremely unusual but brilliant move a human would never have played.

Developing the equivalent of step 2 for LLMs is a key research problem for overcoming the data wall (and, moreover, will ultimately be the key to surpassing human-level intelligence).

All of this is to say that data constraints seem to inject large error bars either way into forecasting the coming years of AI progress. There’s a very real chance things stall out (LLMs might still be as big of a deal as the internet, but we wouldn’t get to truly crazy AGI). But I think it’s reasonable to guess that the labs will crack it, and that doing so will not just keep the scaling curves going, but possibly enable huge gains in model capability.

As an aside, this also means that we should expect more variance between the different labs in coming years compared to today. Up until recently, the state of the art techniques were published, so everyone was basically doing the same thing. (And new upstarts or open source projects could easily compete with the frontier, since the recipe was published.) Now, key algorithmic ideas are becoming increasingly proprietary. I’d expect labs’ approaches to diverge much more, and some to make faster progress than others—even a lab that seems on the frontier now could get stuck on the data wall while others make a breakthrough that lets them race ahead. And open source will have a much harder time competing. It will certainly make things interesting. (And if and when a lab figures it out, their breakthrough will be the key to AGI, key to superintelligence—one of the United States’ most prized secrets.)

Unhobbling

Finally, the hardest to quantify—but no less important—category of improvements: what I’ll call “unhobbling.”

Imagine if when asked to solve a hard math problem, you had to instantly answer with the very first thing that came to mind. It seems obvious that you would have a hard time, except for the simplest problems. But until recently, that’s how we had LLMs solve math problems. Instead, most of us work through the problem step-by-step on a scratchpad, and are able to solve much more difficult problems that way. “Chain-of-thought” prompting unlocked that for LLMs. Despite excellent raw capabilities, they were much worse at math than they could be because they were hobbled in an obvious way, and it took a small algorithmic tweak to unlock much greater capabilities.

We’ve made huge strides in “unhobbling” models over the past few years. These are algorithmic improvements beyond just training better base models—and often only use a fraction of pretraining compute—that unleash model capabilities:

- Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Base models have incredible latent capabilities,26 but they’re raw and incredibly hard to work with. While the popular conception of RLHF is that it merely censors swear words, RLHF has been key to making models actually useful and commercially valuable (rather than making models predict random internet text, get them to actually apply their capabilities to try to answer your question!). This was the magic of ChatGPT—well-done RLHF made models usable and useful to real people for the first time. The original InstructGPT paper has a great quantification of this: an RLHF’d small model was equivalent to a non-RLHF’d >100x larger model in terms of human rater preference.

- Chain of Thought (CoT). As discussed. CoT started being widely used just 2 years ago and can provide the equivalent of a >10x effective compute increase on math/reasoning problems.

- Scaffolding. Think of CoT++: rather than just asking a model to solve a problem, have one model make a plan of attack, have another propose a bunch of possible solutions, have another critique it, and so on. For example, on HumanEval (coding problems), simple scaffolding enables GPT-3.5 to outperform un-scaffolded GPT-4. On SWE-Bench (a benchmark of solving real-world software engineering tasks), GPT-4 can only solve ~2% correctly, while with Devin’s agent scaffolding it jumps to 14-23%. (Unlocking agency is only in its infancy though, as I’ll discuss more later.)

- Tools: Imagine if humans weren’t allowed to use calculators or computers. We’re only at the beginning here, but ChatGPT can now use a web browser, run some code, and so on.

- Context length. Models have gone from 2k token context (GPT-3) to 32k context (GPT-4 release) to 1M+ context (Gemini 1.5 Pro). This is a huge deal. A much smaller base model with, say, 100k tokens of relevant context can outperform a model that is much larger but only has, say, 4k relevant tokens of context—more context is effectively a large compute efficiency gain.27 More generally, context is key to unlocking many applications of these models: for example, many coding applications require understanding large parts of a codebase in order to usefully contribute new code; or, if you’re using a model to help you write a document at work, it really needs the context from lots of related internal docs and conversations. Gemini 1.5 Pro, with its 1M+ token context, was even able to learn a new language (a low-resource language not on the internet) from scratch, just by putting a dictionary and grammar reference materials in context!

- Posttraining improvements. The current GPT-4 has substantially improved compared to the original GPT-4 when released, according to John Schulman due to posttraining improvements that unlocked latent model capability: on reasoning evals it’s made substantial gains (e.g., ~50% -> 72% on MATH, ~40% to ~50% on GPQA) and on the LMSys leaderboard, it’s made nearly 100-point elo jump (comparable to the difference in elo between Claude 3 Haiku and the much larger Claude 3 Opus, models that have a ~50x price difference).

A survey by Epoch AI of some of these techniques, like scaffolding, tool use, and so on, finds that techniques like this can typically result in effective compute gains of 5-30x on many benchmarks. METR (an organization that evaluates models) similarly found very large performance improvements on their set of agentic tasks, via unhobbling from the same GPT-4 base model: from 5% with just the base model, to 20% with the GPT-4 as posttrained on release, to nearly 40% today from better posttraining, tools, and agent scaffolding.

While it’s hard to put these on a unified effective compute scale with compute and algorithmic efficiencies, it’s clear these are huge gains, at least on a roughly similar magnitude as the compute scaleup and algorithmic efficiencies. (It also highlights the central role of algorithmic progress: the 0.5 OOMs/year of compute efficiencies, already significant, are only part of the story, and put together with unhobbling algorithmic progress overall is maybe even a majority of the gains on the current trend.)

“Unhobbling” is what actually enabled these models to become useful—and I’d argue that much of what is holding back many commercial applications today is the need for further “unhobbling” of this sort. Indeed, models today are still incredibly hobbled! For example:

- They don’t have long-term memory.

- They can’t use a computer (they still only have very limited tools).

- They still mostly don’t think before they speak. When you ask ChatGPT to write an essay, that’s like expecting a human to write an essay via their initial stream-of-consciousness.28

- They can (mostly) only engage in short back-and-forth dialogues, rather than going away for a day or a week, thinking about a problem, researching different approaches, consulting other humans, and then writing you a longer report or pull request.

- They’re mostly not personalized to you or your application (just a generic chatbot with a short prompt, rather than having all the relevant background on your company and your work).

The possibilities here are enormous, and we’re rapidly picking low-hanging fruit here. This is critical: it’s completely wrong to just imagine “GPT-6 ChatGPT.” With continued unhobbling progress, the improvements will be step-changes compared to GPT-6 + RLHF. By 2027, rather than a chatbot, you’re going to have something that looks more like an agent, like a coworker.

From chatbot to agent-coworker

What could ambitious unhobbling over the coming years look like? The way I think about it, there are three key ingredients:

1. Solving the “onboarding problem”

GPT-4 has the raw smarts to do a decent chunk of many people’s jobs, but it’s sort of like a smart new hire that just showed up 5 minutes ago: it doesn’t have any relevant context, hasn’t read the company docs or Slack history or had conversations with members of the team, or spent any time understanding the company-internal codebase. A smart new hire isn’t that useful 5 minutes after arriving—but they are quite useful a month in! It seems like it should be possible, for example via very-long-context, to “onboard” models like we would a new human coworker. This alone would be a huge unlock.

2. The test-time compute overhang (reasoning/error correction/system II for longer-horizon problems)

Right now, models can basically only do short tasks: you ask them a question, and they give you an answer. But that’s extremely limiting. Most useful cognitive work humans do is longer horizon—it doesn’t just take 5 minutes, but hours, days, weeks, or months.

A scientist that could only think about a difficult problem for 5 minutes couldn’t make any scientific breakthroughs. A software engineer that could only write skeleton code for a single function when asked wouldn’t be very useful—software engineers are given a larger task, and they then go make a plan, understand relevant parts of the codebase or technical tools, write different modules and test them incrementally, debug errors, search over the space of possible solutions, and eventually submit a large pull request that’s the culmination of weeks of work. And so on.

In essence, there is a large test-time compute overhang. Think of each GPT-4 token as a word of internal monologue when you think about a problem. Each GPT-4 token is quite smart, but it can currently only really effectively use on the order of ~hundreds of tokens for chains of thought coherently (effectively as though you could only spend a few minutes of internal monologue/thinking on a problem or project).

What if it could use millions of tokens to think about and work on really hard problems or bigger projects?

| Number of tokens | Equivalent to me working on something for… | |

| 100s | A few minutes | ChatGPT (we are here) |

| 1000s | Half an hour | +1 OOMs test-time compute |

| 10,000s | Half a workday | +2 OOMs |

| 100,000s | A workweek | +3 OOMs |

| Millions | Multiple months | +4 OOMs |

Even if the “per-token” intelligence were the same, it’d be the difference between a smart person spending a few minutes vs. a few months on a problem. I don’t know about you, but there’s much, much, much more I am capable of in a few months vs. a few minutes. If we could unlock “being able to think and work on something for months-equivalent, rather than a few-minutes-equivalent” for models, it would unlock an insane jump in capability. There’s a huge overhang here, many OOMs worth.

Right now, models can’t do this yet. Even with recent advances in long-context, this longer context mostly only works for the consumption of tokens, not the production of tokens—after a while, the model goes off the rails or gets stuck. It’s not yet able to go away for a while to work on a problem or project on its own.29

But unlocking test-time compute might merely be a matter of relatively small “unhobbling” algorithmic wins. Perhaps a small amount of RL helps a model learn to error correct (“hm, that doesn’t look right, let me double check that”), make plans, search over possible solutions, and so on. In a sense, the model already has most of the raw capabilities, it just needs to learn a few extra skills on top to put it all together.

In essence, we just need to teach the model a sort of System II outer loop30 that lets it reason through difficult, long-horizon projects.

If we succeed at teaching this outer loop, instead of a short chatbot answer of a couple paragraphs, imagine a stream of millions of words (coming in more quickly than you can read them) as the model thinks through problems, uses tools, tries different approaches, does research, revises its work, coordinates with others, and completes big projects on its own.

Trading off test-time and train-time compute in other ML domains

In other domains, like AI systems for board games, it’s been demonstrated that you can use more test-time compute (also called inference-time compute) to substitute for training compute.

If a similar relationship held in our case, if we could unlock + 4 OOMs of test-time compute, that might be equivalent to + 3OOMs of pretraining compute, i.e. very roughly something like the jump between GPT-3 and GPT-4. (I.e., solving this “unhobbling” would be equivalent to a huge OOM scaleup.)

3. Using a computer

This is perhaps the most straightforward of the three. ChatGPT right now is basically like a human that sits in an isolated box that you can text. While early unhobbling improvements teach models to use individual isolated tools, I expect that with multimodal models we will soon be able to do this in one fell swoop: we will simply enable models to use a computer like a human would.

That means joining your Zoom calls, researching things online, messaging and emailing people, reading shared docs, using your apps and dev tooling, and so on. (Of course, for models to make the most use of this in longer-horizon loops, this will go hand-in-hand with unlocking test-time compute.)

By the end of this, I expect us to get something that looks a lot like a drop-in remote worker. An agent that joins your company, is onboarded like a new human hire, messages you and colleagues on Slack and uses your softwares, makes pull requests, and that, given big projects, can do the model-equivalent of a human going away for weeks to independently complete the project. You’ll probably need somewhat better base models than GPT-4 to unlock this, but possibly not even that much better—a lot of juice is in fixing the clear and basic ways models are still hobbled.

By the way, I expect the centrality of unhobbling to lead to a somewhat interesting “sonic boom” effect in terms of commercial applications. Intermediate models between now and the drop-in remote worker will require tons of schlep to change workflows and build infrastructure to integrate and derive economic value from. The drop-in remote worker will be dramatically easier to integrate—just, well, drop them in to automate all the jobs that could be done remotely. It seems plausible that the schlep will take longer than the unhobbling, that is, by the time the drop-in remote worker is able to automate a large number of jobs, intermediate models won’t yet have been fully harnessed and integrated—so the jump in economic value generated could be somewhat discontinuous.

The next four years

Putting the numbers together, we should (roughly) expect another GPT-2-to-GPT-4-sized jump in the 4 years following GPT-4, by the end of 2027.

- GPT-2 to GPT-4 was roughly a 4.5–6 OOM base effective compute scaleup (physical compute and algorithmic efficiencies), plus major “unhobbling” gains (from base model to chatbot).

- In the subsequent 4 years, we should expect 3–6 OOMs of base effective compute scaleup (physical compute and algorithmic efficiencies)—with perhaps a best guess of ~5 OOMs—plus step-changes in utility and applications unlocked by “unhobbling” (from chatbot to agent/drop-in remote worker).

To put this in perspective, suppose GPT-4 training took 3 months. In 2027, a leading AI lab will be able to train a GPT-4-level model in a minute.31 The OOM effective compute scaleup will be dramatic.

Where will that take us?

GPT-2 to GPT-4 took us from ~preschooler to ~smart high-schooler; from barely being able to output a few cohesive sentences to acing high-school exams and being a useful coding assistant. That was an insane jump. If this is the intelligence gap we’ll cover once more, where will that take us?32 We should not be surprised if that takes us very, very far. Likely, it will take us to models that can outperform PhDs and the best experts in a field.

(One neat way to think about this is that the current trend of AI progress is proceeding at roughly 3x the pace of child development. Your 3x-speed-child just graduated high school; it’ll be taking your job before you know it!)

Again, critically, don’t just imagine an incredibly smart ChatGPT: unhobbling gains should mean that this looks more like a drop-in remote worker, an incredibly smart agent that can reason and plan and error-correct and knows everything about you and your company and can work on a problem independently for weeks.

We are on course for AGI by 2027. These AI systems will basically be able to automate basically all cognitive jobs (think: all jobs that could be done remotely).

To be clear—the error bars are large. Progress could stall as we run out of data, if the algorithmic breakthroughs necessary to crash through the data wall prove harder than expected. Maybe unhobbling doesn’t go as far, and we are stuck with merely expert chatbots, rather than expert coworkers. Perhaps the decade-long trendlines break, or scaling deep learning hits a wall for real this time. (Or an algorithmic breakthrough, even simple unhobbling that unleashes the test-time compute overhang, could be a paradigm-shift, accelerating things further and leading to AGI even earlier.)

In any case, we are racing through the OOMs, and it requires no esoteric beliefs, merely trend extrapolation of straight lines, to take the possibility of AGI—true AGI—by 2027 extremely seriously.

It seems like many are in the game of downward-defining AGI these days, as just as really good chatbot or whatever. What I mean is an AI system that could fully automate my or my friends’ job, that could fully do the work of an AI researcher or engineer. Perhaps some areas, like robotics, might take longer to figure out by default. And the societal rollout, e.g. in medical or legal professions, could easily be slowed by societal choices or regulation. But once models can automate AI research itself, that’s enough—enough to kick off intense feedback loops—and we could very quickly make further progress, the automated AI engineers themselves solving all the remaining bottlenecks to fully automating everything. In particular, millions of automated researchers could very plausibly compress a decade of further algorithmic progress into a year or less. AGI will merely be a small taste of the superintelligence soon to follow. (More on that in the next piece.)

In any case, do not expect the vertiginous pace of progress to abate. The trendlines look innocent, but their implications are intense. As with every generation before them, every new generation of models will dumbfound most onlookers; they’ll be incredulous when, very soon, models solve incredibly difficult science problems that would take PhDs days, when they’re whizzing around your computer doing your job, when they’re writing codebases with millions of lines of code from scratch, when every year or two the economic value generated by these models 10xs. Forget scifi, count the OOMs: it’s what we should expect. AGI is no longer a distant fantasy. Scaling up simple deep learning techniques has just worked, the models just want to learn, and we’re about to do another 100,000x+ by the end of 2027. It won’t be long before they’re smarter than us.

Next post in series:

II. From AGI to Superintelligence: the Intelligence Explosion

Addendum. Racing through the OOMs: It’s this decade or bust

I used to be more skeptical of short timelines to AGI. One reason is that it seemed unreasonable to privilege this decade, concentrating so much AGI-probability-mass on it (it seemed like a classic fallacy to think “oh we’re so special”). I thought we should be uncertain about what it takes to get AGI, which should lead to a much more “smeared-out” probability distribution over when we might get AGI.

However, I’ve changed my mind: critically, our uncertainty over what it takes to get AGI should be over OOMs (of effective compute), rather than over years.

We’re racing through the OOMs this decade. Even at its bygone heyday, Moore’s law was only 1–1.5 OOMs/decade. I estimate that we will do ~5 OOMs in 4 years, and over ~10 this decade overall.

In essence, we’re in the middle of a huge scaleup reaping one-time gains this decade, and progress through the OOMs will be multiples slower thereafter. If this scaleup doesn’t get us to AGI in the next 5-10 years, it might be a long way out.

- Spending scaleup: Spending a million dollars on a model used to be outrageous; by the end of the decade, we will likely have $100B or $1T clusters. Going much higher than that will be hard; that’s already basically the feasible limit (both in terms of what big business can afford, and even just as a fraction of GDP). Thereafter all we have is glacial 2%/year trend real GDP growth to increase this.

- Hardware gains: AI hardware has been improving much more quickly than Moore’s law. That’s because we’ve been specializing chips for AI workloads. For example, we’ve gone from CPUs to GPUs; adapted chips for Transformers; and we’ve gone down to much lower precision number formats, from fp64/fp32 for traditional supercomputing to fp8 on H100s. These are large gains, but by the end of the decade we’ll likely have totally-specialized AI-specific chips, without much further beyond-Moore’s law gains possible.

- Algorithmic progress: In the coming decade, AI labs will invest tens of billions in algorithmic R&D, and all the smartest people in the world will be working on this; from tiny efficiencies to new paradigms, we’ll be picking lots of the low-hanging fruit. We probably won’t reach any sort of hard limit (though “unhobblings” are likely finite), but at the very least the pace of improvements should slow down, as the rapid growth (in $ and human capital investments) necessarily slows down (e.g., most of the smart STEM talent will already be working on AI). (That said, this is the most uncertain to predict, and the source of most of the uncertainty on the OOMs in the 2030s on the plot above.)

Put together, this means we are racing through many more OOMs in the next decade than we might in multiple decades thereafter. Maybe it’s enough—and we get AGI soon—or we might be in for a long, slow slog. You and I can reasonably disagree on the median time to AGI, depending on how hard we think achieving AGI will be—but given how we’re racing through the OOMs right now, certainly your modal AGI year should sometime later this decade or so.

Predictions they’ve made every year for the last decade, and which they’ve been consistently wrong about…↩

From SSC: Janelle Shane asks GPT-2 its ten favorite animals:

Prompt: My 10 favorite animals are: 1.

My ten favorite animals are:

Zebras with a white scar on the back

Insiduous spiders and octopus

Frog with large leaves, hopefully black

Cockatiel with scales

Razorbill with wings hanging about 4 inches from one’s face and a heart tattoo on a frog

Cockatric interlocking tetrabods that can be blind, cut, and eaten raw:

Black and white desert crocodiles living in sunlight

Zebra and many other pea bugs↩From the GPT-2 paper, Section 3.6.↩

I mean clunky old GPT-3 here, not the dramatically-improved GPT-3.5 you might know from ChatGPT.↩

And no, these tests aren’t in the training set. AI labs put real effort into ensuring these evals are uncontaminated, because they need good measurements in order to do good science. A recent analysis on this by ScaleAI confirmed that the leading labs aren’t overfitting to the benchmarks (though some smaller LLM developers might be juicing their numbers).↩

In the original paper, it was noted: “We also evaluated humans on MATH, and found that a computer science PhD student who does not especially like mathematics attained approximately 40% on MATH, while a three-time IMO gold medalist attained 90%, indicating that MATH can be challenging for humans as well.”↩

A coauthor notes: “When our group first released the MATH dataset, at least one [ML researcher colleague] told us that it was a pointless dataset because it was too far outside the range of what ML models could accomplish (indeed, I was somewhat worried about this myself).”↩

Here’s Yann LeCun predicting in 2022 that even GPT-5000 won’t be able to reason about physical interactions with the real world; GPT-4 obviously does it with ease a year later.

Here’s Gary Marcus’s walls predicted after GPT-2 being solved by GPT-3, and the walls he predicted after GPT-3 being solved by GPT-4.

Here’s Prof. Bryan Caplan losing his first-ever public bet (after previously famously having a perfect public betting track record). In January 2023, after GPT-3.5 got a D on his economics midterm, Prof. Caplan bet Matthew Barnett that no AI would get an A on his economics midterms by 2029. Just two months later, when GPT-4 came out, it promptly scored an A on his midterm (and it would have been one of the highest scores in his class).↩On the diamond set, majority voting of the model trying 32 times with chain-of-thought.↩

And it’s worth noting just how consistent these trendlines are. Combining the original scaling laws paper with some of the estimates on compute and compute efficiency scaling since then implies a consistent scaling trend for over 15 orders of magnitude (over 1,000,000,000,000,000x in effective compute)!↩

A common misconception is that scaling only holds for perplexity loss, but we see very clear and consistent scaling behavior on downstream performance on benchmarks as well. It’s usually just a matter of finding the right log-log graph. For example, in the GPT-4 blog post, they show consistent scaling behavior for performance on coding problems over 6 OOMs (1,000,000x) of compute, using MLPR (mean log pass rate). The “Are Emergent Abilities a Mirage?” paper makes a similar point; with the right choice of metric, there is almost always a consistent trend for performance on downstream tasks.

More generally, the “scaling hypothesis” qualitative observation—very clear trends on model capability with scale—predates loss-scaling-curves; the “scaling laws” work was just a formal measurement of this.

↩1. Gemini 1.5 Flash scores 54.9% on MATH, and costs $0.35/$1.05 (input/output) per million tokens. GPT-4 scored 42.5% on MATH prelease and 52.9% on MATH in early 2023, and cost $30/$60 (input/output) per million tokens; that’s 85x/57x (input/output) more expensive per token than Gemini 1.5 Flash. To be conservative, I use an estimate of 30x cost decrease above (accounting for Gemini 1.5 Flash possibly using more tokens to reason through problems).

2. Minerva540B scores 50.3% on MATH, using majority voting among 64 samples. A knowledgeable friend estimates the base model here is probably 2-3x more expensive to inference than GPT-4. However, Minerva seems to use somewhat fewer tokens per answer on a quick spot check. More importantly, Minerva needed 64 samples to achieve that performance, naively implying a 64x multiple on cost if you e.g. naively ran this via an inference API. In practice, prompt tokens can be cached when running an eval; given a few-shot prompt, prompt tokens are likely a majority of the cost, even accounting for output tokens. Supposing output tokens are a third of the cost for getting a single sample, that would imply only a ~20x increase in cost from the maj@64 with caching. To be conservative, I use the rough number of a 20x cost decrease in the above (even if the naive decrease in inference cost from running this via an API would be larger).↩Though these are inference efficiencies (rather than necessarily training efficiencies), and to some extent will reflect inference-specific optimizations, a) they suggest enormous amounts of algorithmic progress is possible and happening in general, and b) it’s often the case that an algorithmic improvements is both a training efficiency gain and an inference efficiency, for example by reducing the number of parameters necessary.↩

GPT-3: $60/1M tokens, GPT-4: $30/1M input tokens and $60/1M output tokens.↩

Chinchilla scaling laws say that one should scale parameter count and data equally. That is, parameter count grows “half the OOMs” of the OOMs that effective training compute grows. At the same time, parameter count is intuitively roughly proportional to inference costs. All else equal, constant inference costs thus implies that half of the OOMs of effective compute growth were “canceled out” by algorithmic win.

That said, to be clear, this is a very naive calculation (just meant for a rough illustration) that is wrong in various ways. There may be inference-specific optimizations (that don’t translate into training efficiency); there may be training efficiencies that don’t reduce parameter count (and thus don’t translate into inference efficiency); and so on.↩Gemini 1.5 Flash ranks similarly to GPT-4 (higher than original GPT-4, lower than updated versions of GPT-4) on LMSys, a chatbot leaderboard, and has similar performance on MATH and GPQA (evals that measure reasoning) as the original GPT-4, while landing roughly in the middle between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 on MMLU (an eval that more heavily weights towards measuring knowledge).↩

For example, this paper contains a comparison of a GPT-3-style vanilla Transformer to various simple changes to architecture and training recipe published over the years (RMSnorms instead of layernorm, different positional embeddings, SwiGlu activation, AdamW optimizer instead of Adam, etc.), what they call “Transformer++”, implying a 6x gain at least at small scale.↩

If we take the trend of 0.5 OOMs/year, and 4 years between GPT-2 and GPT-4 release, that would be 2 OOMs. However, GPT-2 to GPT-3 was a simple scaleup (after big gains from e.g. Transformers), and OpenAI claims GPT-4 pretraining finished in 2022, which could mean we’re looking at closer to 2 years worth of algorithmic progress that we should be counting here. 1 OOM of algorithmic efficiency seems like a conservative lower bound.↩

At the very least, given over a decade of consistent algorithmic improvements, the burden of proof would be on those who would suggest it will all suddenly come to a halt!↩

The economic returns to a 3x compute efficiency will be measured in the $10s of billions or more, given cluster costs.↩

And just rereading the same textbook over and over again might result in memorization, not understanding. I take it that’s how many wordcels pass math classes!↩

One other way of thinking about it I find interesting: there is a “missing-middle” between pretraining and in-context learning. In-context learning is incredible (and competitive with human sample efficiency). For example, the Gemini 1.5 Pro paper discusses giving the model instructional materials (a textbook, a dictionary) on Kalamang, a language spoken by fewer than 200 people and basically not present on the internet, in context—and the model learns to translate from English to Kalamang at human-level! In context, the model is able to learn from the textbook as well as a human could (and much better than it would learn from just chucking that one textbook into pretraining).

When a human learns from a textbook, they’re able to distill their short-term memory/learnings into long-term memory/long-term skills with practice; however, we don’t have an equivalent way to distill in-context learning “back to the weights.” Synthetic data/self-play/RL/etc are trying to fix that: let the model learn by itself, then think about it and practice what it learned, distilling that learning back into the weights.↩That’s the magic of unsupervised learning, in some sense: to better predict the next token, to make perplexity go down, models learn incredibly rich internal representations, everything from (famously) sentiment to complex world models. But, out of the box, they’re hobbled: they’re using their incredible internal representations merely to predict the next token in random internet text, and rather than applying them in the best way to actually try to solve your problem.↩

See Figure 7 from the updated Gemini 1.5 whitepaper, comparing perplexity vs. context for Gemini 1.5 Pro and Gemini 1.5 Flash (a much cheaper and presumably smaller model).↩

People are working on this though!↩

Which makes sense—why would it have learned the skills for longer-horizon reasoning and error correction? There’s very little data on the internet in the form of “my complete internal monologue, reasoning, all the relevant steps over the course of a month as I work on a project.” Unlocking this capability will require a new kind of training, for it to learn these extra skills.

Or as Gwern put it (private correspondence): “‘Brain the size of a galaxy, and what do they ask me to do? Predict the misspelled answers on benchmarks!’ Marvin the depressed neural network moaned.”↩System I vs. System II is a useful way of thinking about current capabilities of LLMs—including their limitations and dumb mistakes—and what might be possible with RL and unhobbling. Think of this way: when you are driving, most of the time you are on autopilot (system I, what models mostly do right now). But when you encounter a complex construction zone or novel intersection, you might ask your passenger-seat-companion to pause your conversation for a moment while you figure out—actually think about—what’s going on and what to do. If you were forced to go about life with only system I (closer to models today), you’d have a lot of trouble. Creating the ability for system II reasoning loops is a central unlock.↩

On the best guess assumptions on physical compute and algorithmic efficiency scaleups described above, and simplifying parallelism considerations (in reality, it might look more like “1440 (60*24) GPT-4-level models in a day” or similar).↩

Of course, any benchmark we have today will be saturated. But that’s not saying much; it’s mostly a reflection on the difficulty of making hard-enough benchmarks.↩